Tree Painting as an Esoteric Deed

By Dennis Klocek 8 min read

This article addresses the gardeners out there who have a little time to engage in a practice that might seem like at total waste of time to a busy agriculturalist. Ever since I read an article in an old Bio-Dynamic magazine on the blood and milk method I have been trying to work out a superior tree paste for fruit trees. The blood and milk method was, I think, a Swedish method where blood from slaughter livestock was mixed with water and clay and painted on the trees in the early spring before the buds were stirring. Then as the flowers were falling and the little fruits were being set skim milk was sprayed onto the little fruits to form a skin on them to protect them from the ovipositors of insect seeking to plant larvae in the fruits. In my mind this linked to the tree paste procedures being advocated at that time in Bio-Dynamic circles.

The typical indication was to mix pottery clay and manure and the Bio-Dynamic preps and paint that mixture on the trees to enhance the vitality of their cambium. This made sense to me but the mixture of manure and clay and water left a lot to be desired in the realm of “paint”. My training is as a painter rebelled at the application of this intense brick like material to trees and calling it “paint”. It was horrible to apply and it washed off in the first rain leaving a gritty mess on the trees.

So after a visit to Japan and seeing the fruit trees in the public parks lovingly wrapped in strips of burlap to protect them I thought of the idea of dipping strips of burlap in the stiff mass of clay and manure and then wrapping the trees in that so that the stuff would stick to the trees when it rained. That worked for a few years and the trees seemed to benefit. The trees I was working with were mostly older peaches and one old apricot. The burlap seemed to be the answer to keeping the “paint’ on the trees during the winter rains. Then we planted a few younger trees that I dutifully wrapped in burlap and my mixture. The young trees amazed us with the vitality of their growth especially the plums that grow so well here in the central valley of California. Unfortunately they grew so well that the burlap, that usually rots in one season dug into the cambium of the trees during the summer and they died as a result of the too vigorous growth combined with the restriction of the burlap on their trunks.

After losing these trees, I was really determined to do something about the funky tree paint. In my graduate studies towards a degree in painting I had taken a number of materials and methods courses from a master technician in ancient painting materials. Ancient painters used alchemical knowledge to make their materials. Later an interest in alchemy kept this study alive in me in the form of many experiments with materials in gardening technology. These two streams of knowledge allowed me to research the properties of tree paint from fruitful angles.

First, the tree paint had to be nutritious to the cambium of the tree. This meant including manure in the paint. I settled on finely sieved horse manure because it was available and because it broke down into a fine dust like form. This was the basis of the paint. Then I added a half pint of honey as an emulsifier, and stirred the fine manure into a paste with the honey. Next the clay was added as dry clay and the mixture quickly became heavy and too thick for mixing. What was needed was some form of liquid that would support the formation of a paint-like surface that would be water resistant if not actually water proof. For that I needed something that would provide a source of nutrition for the cambium but also form a skin to ward off the elements.

In my materials studies I had learned that in ancient China the artisans who made decorative screens used a mixture of pig blood and bone meal and the powdered skin of rabbits to create a fine and durable surface on which to put their more precious pigments. The pig blood and the bone meal mixed into a paste was then wetted with a solution of rabbit skin glue to create a thin paste or gesso that would not react to the moisture of the atmosphere once it had dried. A similar technique, used by farmers in the colonial United States, was employed when they wanted to paint their barns. Lacking the paints that are available today they used a technique for making barn paint that was very similar to the Chinese paints made for their screens. The farmers mixed pig blood and skimmed milk together to create a paint that turned bright red. This red color from the pig’s blood is the source of the red barns across America. The skimmed milk provided a skin for the paint composed of a substance called casein. The casein held the pigment in place by providing a film of toughened milk protein that was water resistant, if not actually water proof. This is like having a watch that is water resistant but not water-proof. The pig blood casein paint would weather off of the boards of the barn over time, but would provide some protection against the elements for a time.

Related to this was the manufacture of casein glue in Egypt. The furniture and the wood- jointing of the sarcophagi of the pharaohs was made with a glue made from cottage cheese rendered into a gluey form by the addition of lime. The lime causes the casein protein to come out of the cottage cheese and form a gluey substance that constitutes superior wood glue and also a superior source of binders in paint. The paint used by illustrators of books in the past was often a casein paint called gouache. It is an opaque watercolor. Elmer’s glue has a cow on the label because the glue in the bottle is derived from casein or milk protein. Milk derived casein glue was the glue of choice of the ancient world.

So, back to the pursuit of an ideal tree paint. The manure and clay mixture was dissolved with a solution of skim milk and blood meal. Half a bag of blood meal to a quart of skim milk was mixed into a gallon of sifted horse manure and a gallon of dry pottery clay. To this mixture was added a quart of cottage cheese and a cup of honey. Then enough skim milk was added to make the mixture into slurry, so that is could be mixed into the consistency of paint. In this mixture the blood and milk and casein and manure and clay could work together to form paint with skin forming properties to ward off the elements as well as nutritional properties to help the trees. As an addition to the mix I add about a pound of hoof and horn meal for the fibrous nature of this material and about a pound and a half of bone meal. The bone and horn represent the center and periphery of the animal organism and they add a calcium/silica polarity to the finished paint that completes and harmonizes the animal gestures of the blood and milk. The honey was added to this mix to help emulsify it and aid in the mixing process. Nettle water from decayed nettles was also on hand as a wetting agent to keep the proper consistency.

Enough of the mixture was made to fill a five- gallon bucket so that mixing could be done in an effective way. After a thorough mixing came the fermentation process. The buckets were sealed with a tight lid. After a few days the top blew off of two of the buckets so a heavy rock was added to help keep the lids on the actively bubbling mix. After six months the bucket could only be opened in the dead of the night. The whole neighborhood would wonder what died in the vicinity as a result of any mixing process at this time. Foul bubbles and strange and potent odors came out of the bucket while it was working at this stage. Don’t even think of putting this toxic mess on a tree. Even after a year it was possible to open the bucket only if you snuck up on it with out letting it know you were coming. However, after two years the foulness had left the mixture and the paint was smooth and lovely. The ferment had rendered all elements of the paint into an integrated whole. Of course, this paint always will have a bit of a sea-shore at low tide tang to it for a week or so after application, but after two years in the bucket it is a beautifully textured paint that allows for a sensual ritual in the spring of the painting of the trees. The smell is tolerable but the effects are remarkable. I usually mix five gallons each year so that it can rest for two years until I can use it.

When this paint has fully fermented it turns a delicate gray color and has the texture of the finest acrylic paint that has a lot of tack and body. A fat old three inch bristle house painting brush caresses this mixture like it was the finest, thick and creamy interior latex. Starting at the bottom of the apple, apricot, Asian pear, and nectarine trees on the property I paint a primer layer from the trunk to the branches as big as my thumb in the early spring as the buds are swelling. This first primer coat fills in the grooves in the bark and any sore spots and promotes rapid cambium growth as the saps rise up from the root in the early spring. A few weeks later I give another coat of paint to the same trees. This time the succulent dripping quality of the clay and casein paint makes for a sculptural/painting sensual experience as the paint flowing off of the brush forms ridges of clay around each branch. The primer layer holds these added layers in a very sensual and artistic manner. These layers of paint can be built up as a kind of art form, sculpting the fluid clay and casein with the brush and forming a nutritive layer for the fruit trees that is at once incredibly sensual and rationally effective. Often when it is too early to be digging the earth in the spring, the elementals of my garden can be treated to a surge of tree painting that supports the kick off for the new growing season. The paint made in this way hugs the branches as it drips off of the brush and oozes down the branch towards a crotch in the tree. The brush can then smooth out the ripples of the still semi-liquid viscous paint because of the adhesive forces of the clay and casein in the paint. The nutrients in the paint form a second skin to feed the fruits still contained within the slumbering buds. The casein reacts to the blood and bone constituents in the mix by forming a skin that keeps the paint intact during sun and rain episodes of early spring. The paint of this year has held on through more than a week of rain totaling almost four inches. It still has not deteriorated and looks fresh and smooth. When it gets wet it turns dark again and swells but when it dries out it looks firm without a lot of peeling. There is some cracking but the paint tends to hold on to the bark so that a few early rains in the spring don’t wash the paint from the trees so that they can carry their extra cambium layers through the times when they develop the fruit that has set on their branches. After the summer, in the first few storms of winter, the paint drops off of the trees and forms a subtle fertilizer as it disperses on the ground. Then in February as the new buds swell it is time once again to perform the ritual of painting the trees as the elemental beings waken and celebrate the return of the life forces by opening the flowers and setting the fruits on the trees.

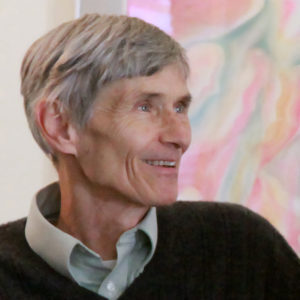

Dennis Klocek

Dennis Klocek, MFA, is co-founder of the Coros Institute, an internationally renowned lecturer, and teacher. He is the author of nine books, including the newly released Colors of the Soul; Esoteric Physiology and also Sacred Agriculture: The Alchemy of Biodynamics. He regularly shares his alchemical, spiritual, and scientific insights at soilsoulandspirit.com.

Similar Writings

The Alchemical Worldview

Esoterically the central task of the human being is to achieve what is known as the second birth, or what is known to students of Rudolf Steiner as the birth of the “I” being. Our first birth is into a body of flesh. This is given to us by nature working through our parents. The…

Silica and Clay Polarity

Silica is the light pole in the minerals. It is a kind of flowering process in the mineral realm since silica in plant growth enhances the refined properties that light brings to plants. Photosynthesis requires light for its action. The light interacts with the flavonoids (phenols and tannins) and anthocyanins (blue and red pigments that…