Experimental Process for Enhancing Drought Tolerance and Fungus Resistance in Plants

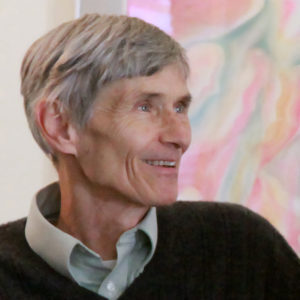

By Dennis Klocek 11 min read

In the life of a plant alcohols play an important role in the maturation and fruiting process. They also form the basis for the protective wax cuticle that keeps the plant free from insect and fungus attack. Plant wax in the form of the cuticle surrounding the surfaces of leaves and stems of plants also allows the plant to retain moisture in times of drought. The wax in the cuticle is the end product of alcohol metabolism as sugar is metabolized in the plant. Roughly, the sequence is sugar, alcohol as ethanol, alcohol as oil or fat, and alcohol as wax. These stages can be mirrored in the classical sequences of sal, sulf and mercury. In the alchemical process these three aspects are the guiding principles to the formation of a spagyric essence or elixer. The sal aspect is any solid or precipitate that arises in the interaction. The sulf aspect is any oily or greasy substance that arises in the interaction. Oil or grease was considered by the alchemists to be what they called a compound of moist fire. The mercury in the compound is the elixer that allows the sal to modify into sulf and vice versa. These principles can be used to construct a liquid spray that is designed to augment the wax forming processes in plants in order to strengthen resistance to mildew and to ease drought stress.

There are two forms of plant wax. Epi-cuticular, which is a hard wax that forms mostly on the surfaces of the plants. It is formed from what are known as long chain alcohols. Hard wax is a protection against insect and fungal invasion. It is a sal or precipitating process in that the abundant carbon that makes up the hard wax alchemically would be classed as an earth or precipitate. By contrast, intra-cuticular wax is softer and is formed from short chain alcohols. Soft wax is found inside the leaf surfaces and is active in the action of the stoma of the plant. The stoma regulate the loss of fluids when the plant is under stress from drought conditions. Soft wax has more of the sulf or greasy quality in that is more of an emulsion than a hard shell. In members of the mustard family and the mint family substances that enhance wax production are found in abundance. In grapes, the bloom that forms on the grape berry itself is a soft wax.

ALCHEMICAL PRINCIPLES

Using these ideas the intent of this experiment is to design an alchemically designed wax elixer that would serve both to lessen the effects of mildew on grape vines early in the growing year and then to protect the plant itself and the berry from drying out in the ripening stages when there is often the threat of extreme heat. During ripening, wine growers are reluctant to apply water because they don’t want to intrude on the natural ripening process of the grapes. Both of these difficulties would be aided by having the grape produce more of both kinds of wax. The design of the wax elixer for use in grapes is to enhance the wax forming process in the young plants. In the wax elixer, the structure will involve several versions of the fundamental sal, sulf and mercury motif. The alchemical sal makes use of a gem. It is formed from the preparation of finely ground amethyst in a matrix of silica. The alchemical mercury is red wine that provides the primary alcohol content. The alchemical sulf in the wax essence is provided by several herbs that are specialists at organizing the production of the essential acids that serve as the foundation for the wax metabolism processes.

The alchemical sal is made by the fine grinding of amethyst crystals on a glass slab. The gesture of the amethyst as a crystal matrix is what is known as a double twin or Brazil twin. Standard quartz crystals bend light beams sent through them either in one direction or another depending upon the forces acting on them in their initial development when they are in a viscous stage. The bending of the light is called handedness. Handedness is created by unique molecular motions given to the mucous-like “rock milk” that gives birth to the gem forms of silica. In contrast to pure quartz, in the amethyst the light is bent in two directions or “hands” simultaneously. The inner structure of amethyst has one molecular layer that is right handed and the next molecular layer is left handed. This oscillating pattern continues though the entire crystal giving it a remarkable inner integrity and stability that literally “weaves” light. The function of the amethyst crystals in the wax essence is to create an extremely fine layer of crystalline silicate on the leaves to enhance the absorption of light in a regulatory fashion.

It also is interesting to note that the fine layer of hard wax on the surfaces of leaves is microcrystalline. When seen under a high powered microscope the tetrahedral microcrystalline wax pyramids on the surface of, for instance, a lotus leaf bear a striking resemblance to the woven crystalline tetrahedral “double handed” form of the amethyst.

GEM FERMENT

The ground amethyst is then processed in the red wine, to which several herbal substances have been added. That step contributes both the mercurial form of alcohol and the phenolics that are part of the process of transformation from oil to wax in the evolution of primary alcohols in a maturing plant. The function of the herbs is to combine with the alcohol in the wine to create a solution that promotes formation of waxes that give the plant leaf protection from the stress of drought conditions. Chemically the formation of a plant wax involves the transformation of an alcohol. Certain plants are specialists at performing this transformation. They each contribute a particular aspect of the transformation and will be described here in the context of what they add to the mix of the wine and the amethyst. Some of them bring an abundance of wax and others provide for the rapid and complete transformation of the hydrocarbons in the plant into wax.The following herbs can be introduced into red wine for fermentation. They have been chosen because they too are specialists at wax formation and metabolism. . Ursolic and oleanolic acid are the components in plants that give rise to wax formation. Both of them are antimicrobial and mobilize the metabolism of plants towards wax formation.

DROUGHT TOLERANCE

Ursolic acid is found in great amounts in plants of the labiate family such as basil, rosemary and oregano. It facilitates the formation of soft waxes found inside the leaves that protect against drought. These waxes can be acted on by the alcohol in the wine as a prophylactic against drought. The herbs serve as a kind of wax base for the ferment.

ANTI-FUNGAL

Oleanolic acid aids in the formation of hard waxes that ward off fungal invasions. It is found in two plants common to California, the olive and the common field rocket. The leaf of the olive is very rich in this waxy precursor and anti fungal substance. The field rocket is part of the group Arabidopsis that is related to the mustards. The strong essential oils of this plant are a potent fungicide and they work in a way that is analogous to the way that a plant’s natural defenses work. As analogs they enable the plant to uptake the waxes and oils more effectively. Penetration of cuticle is important for foliar sprays. Arabidopsis has been used by plant scientists to study the action of sprays and leaf surfaces due to its clear absorptive processes and well developed cuticle structures. Taken together these plants when added in volume to wine produce a solution that is a chemically potent elixer or model for strengthening the cuticle.

AMOUNTS

Regarding the amounts of the herbs the more herbs introduced to the wine the stronger the elixer. It will certainly be easier to get large amounts of rosemary and olive leaves compared to penny cress. The soft wax sources such as rosemary leaves can be put in the wine in abundance. The solution for the extract: Using 25 gal of wine for the fluid the rest of the space in a 50 gal container would be made up of the herbs. More herbs make a more concentrated elixer.

Because it can be gathered in bulk it can be thought that the olive leaves provide the bulk of the material for the oleanoic acid process. They can be added as much as can be gathered. Likewise rosemary or basil leaves can be cultivated in abundance for the soft wax additions. The addition of two pounds of powdered cinnamon to fifty gallons of elixer is also very beneficial for the purposes of mildew abatement.

After the ferment has been established for a few months the liquid herbal extraction can be used in a ball mill or rock tumbler as the liquid used to lubricate the grinding process. The finely ground amethyst can then be placed in the chamber with a larger amount of finely ground quartz. The machine can then be run for a week or so to potentize the particles in the herbal extract medium. The constitution of the material in the mill should be like slurry in order to facilitate grinding. Crushing and initial grinding of the amethyst crystals into a coarse powder can be done with a metal mortar and pestle to facilitate the process. Once the amethyst is finely ground add the liquid and potentize into a slurry.

DILUTION

For use, the finely dispersed gems in the finished elixer can then be stirred vigorously each time and diluted in amounts of one half ounce to a half a gallon of water. For mildew protection the addition of commercial kelp products also is and aid in the spring. See the related article on peach leaf curl and mildew for timing of the sprays. For mildew the essence can also be alternated with a solution of boiled equisetum arvense. Half a pound of dried horsetail is boiled for an hour in three gallons of water the poured over a bed of fresh nettles for ten minutes and then poured off and left to ferment for a month in a cool dark place.

For mildew protection, in general it is better to spray one type of prophylactic substance one time and another the next time. This prevents the organism from adapting and developing a resistance to the spray. A very good alternate to the wax elixer would be equisetum tea warmed and then poured on a bed of fresh cut chives to sit for ten minutes. Then add to that some sticker to make a spray.

MOON

All herbs for these preparations are gathered when the moon is somewhere near the dark and in an air constellation. That puts the focus of the energies in an inwardly concentrating gesture in the dried plant material.

For heat stress in grapes the elixer can be sprayed in the evening at veraison or ripening when heat spikes are threatening the vines. Spraying in the afternoon on days when the moon is running through water helps for drought protection when there is no threat of mildew.

For mildew protection in the spring start spraying the vine trunks three weeks before budbreak. Spray in the early mornings on days when the moon is moving through air or fire. The moon moves through fire trines or air trines in ten day intervals. Rhythmically the moon moves through air for two and a half days then through water for two and a half days then through fire for two and a half days. Spraying every four days would set this protective pattern into the vines in mid March. Similar patterns of sprays for peach leaf curl and related diseases can be developed.

The following directions for powdery mildew on grapes can also be followed by fungal diseases of fruit trees since the pathogenic patterns are similar for powdery mildew and peach leaf curl.

POWDERY MILDEW ON GRAPES

There are two important times for the powdery mildew fungus. The first is the primary phase of the infection near bud break with temperatures between 50° and 59° and rain for 12 to 15 hrs. Vines are susceptible at bud break when temperatures and humidity provide these conditions. Powdery mildew over-winters in the crevices of bark or in buds as a group of thin threads on which there form small black fruiting bodies (cleistothecia / think wombs). These are found on the bark and in dormant buds. In spring, sexual spores (ascospores / think embryos) that have remained dormant in the small black fruiting bodies during winter, are released when the temperature reaches 59° F ( Jan. Calistoga / Feb. Carneros) and there is continuous rain for 12 to 15 hrs. These conditions rupture the fruiting bodies and release the sexual spores. Once released, the sexual spores spread by air and infect any green surface they land on. This initial spore release phase starts just prior to bud break and continues until blooming.

Within a week after initial infection by the sexual spores, the fungus mycelia produced by the sexual spores forms a fruiting body but this time, according to the alternation of generations, the fungus produces asexual spores (conidia / think clones). The clones soon germinate and send out mycelia. This is the second or spreading phase of the fungus. The clones do not need rain to germinate and spread, temperature being the most important factor in the second phase. The white mycelia of the clones are the recognizable signature of the powdery mildew. Free rainfall at this stage is actually detrimental to the conidia / clones. However, high relative humidity at this time is beneficial to the spread of the conidia / clones. One sexual spore / embryo can produce hundreds of thousands of asexual spores /clones, a point to remember when forming strategies to defeat the fungus.

With the second phase, fruits are highly susceptible, with epidemics when there are three consecutive days of six hours with temperatures between 75°and 85° (May,Calistoga – June, Carneros). These temperatures are often the situation immediately before pre-bloom and a month after. This makes the time just before bloom the most critical spraying time. Susceptibility declines rapidly after two or three weeks after bloom as daytime temperatures in the low 90s will restrict the spread of mycelia. This die off can be compromised by moderate daytime temperatures or high relative humidity from lingering morning fog. Fruits are susceptible from flowering until the berries reach 12 or 15 Brix.

SUMMARY

The over wintering phase begins in the late summer and early fall as new sexual spores /embryos are formed on infected leaves, shoots and berries. With the first fall rains the new crop of sexual spores is washed into crevices in the bark and near the buds and form over-wintering mycelia. Spraying before the first fall rains after harvest is a useful beginning for a control strategy. The sexual spores /embryos remain quiescent in the bark near the buds until favorable moisture and temperatures conditions release the spores near bud break. Spraying a second time just prior to bud break is the next stage of control strategy for the first phase.

The second or expansion phase reaches maximum just prior to flowering when temperatures are more moderate. This will continue throughout the season as long as moderate temperatures (70° to 85°F) exist for three consecutive days for six hours a day.

Alternating fungicides with different modes of action is essential to prevent pathogen populations from developing resistance to fungicides. Do not apply more than two sequential sprays of a particular fungicide before alternating with a fungicide that has a different mode of action.

Dennis Klocek

Dennis Klocek, MFA, is co-founder of the Coros Institute, an internationally renowned lecturer, and teacher. He is the author of nine books, including the newly released Colors of the Soul; Esoteric Physiology and also Sacred Agriculture: The Alchemy of Biodynamics. He regularly shares his alchemical, spiritual, and scientific insights at soilsoulandspirit.com.

Similar Writings

Video Series: Plant Sprays

This new series is the result of several days spent with Dennis over 6 months, in which he shared how the plant sprays he uses affect growth, how to make them, and some tricks he’s learned along the way. Video 1: Why Use Plant Sprays? Secrets to abundant oil, flower and fruit production in the…

Creating a “Maturing” plant spray for cool weather veggies like lettuce, leeks and cabbage

Creating the Parsley Extract for the “maturing” spray.