Proof Magazine Interview of Dennis – 2001

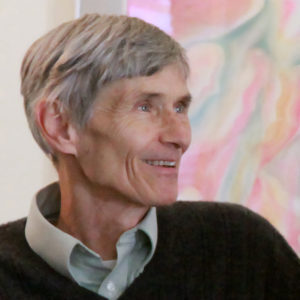

By Dennis Klocek 36 min read

Dennis Klocek, in conversation with Neil Martinson

NM: Dennis, you're the head of Goethean (Consciousness) studies here at Rudolf Steiner College, and I wanted to talk to you about Goethe and Goethean studies. To start things off: I think a lot of existential problems people run into in the world result from doubts about the objective reality of form, which seem to stem from our culture's inability to differentiate analytical and holistic thinking. For instance, analytical thinking views the human form as a bunch of separate elements, whereas the holistic view sees the whole entity. Could you share some insights?

DK: Many Goetheanists believe that Goethe started all of that type of holistic thinking, but really Goethe was in a long line of seers, including Paracelsus and Jacob Boehme in what is known as the Mystery tradition, in which it was understood that behind the phenomena of the world there was another archetypal world acting, and that what we saw manifest in the world was the husk of their activity. Goethe, as a scientist, developed his thinking out of his poetic muse, so to speak, or his poetic experience of the world. He thought there needed to be a science that had the mood of the mysteries to it, the poetic mood, and he was not alone. There were many people at the time of Goethe who were also echoing that desire, because of the rise of modern reductionist empiricism in the sciences at that time. Those souls were the Romantic poets.

Rational science was just blooming, and Goethe was following in the footsteps of many people who felt that (the dogma of) reason and causality was just one way to look at the world. The other way to look at the world had a spiritual quality to it. It had what today we would call a numinous or even sacred or holy quality. The numinous quality is something supernatural to the mundane aspects of an object which you are observing that arouses elevated feelings which are perceived inwardly.The correct way of working inwardly can develop perception of the numinous, or what Carl Jung called “the Holy” aspects of reality. With such capacities, you can perceive that which is spiritually active within the phenomenon, rather than what is just causal or physical. Perception of the numinous aspects of things is linked to teleological thinking. In teleological thinking, you take what would be the final result in a reductionist experiment as the initial and primary point, the essential fact. In teleological thinking, you reverse the sequencing of the becoming of a phenomenon. Instead of constructing an hypothesis based upon data sets and trying to get to meaning, in teleological thinking you start with the experience of meaning and let the data fit in where it may.

NM: I think it has to do with the belief in, or the study of design or purpose in nature. And there is a whole reaction against teleology.

DK: Of course, that's reductionist empirical science doing the reacting. But today we have the teleological principle at work in aspects of the quantum theory. People are finding that if a specific particle is found to exist then by the laws of symmetry there must be a counter or anti-particle present somewhere in order for the reality of the sub atomic world to hold together theoretically.

So the physicists have to say, well here's a particle that has a certain charge and behaves in a certain way, but because of how the universe is constructed, we have to posit the existence of an anti-neutrino, or an anti-quark, because our thinking requires symmetry. That's teleological. It doesn't come out of your experiment or your data sets, it comes out of an inner experience in which you know that there is a larger field of meaningful activity (like symmetry) that you can sense is behind everything which you are observing, and so you try to intuit out of that sense of meaningfulness how the event unfolded in the beginning.

In Goethe's time there were other people who were working in this way. Luke Howard, for instance, the man who first made the classifications of clouds that we have today, cirrus and cumulus and so forth. He was a phenomenologist, although it wasn't called that at the time, and Goethe was very interested in Howard's work with the atmosphere, because he felt a kindred soul in the way that he was approaching the problem. Goethe coined the word morphology, which you could say means the word-like nature of the body, what the body is saying, what it speaks or we could even say what the body “means”.

NM: Rather than looking at the world of phenomena as a bunch of sense data, seeing it as meaning.

DK: Right. If you were to go and study botany in a university, right off you would have a list of terms that you would have to memorize. That list would be what an alchemist would call the corpse, or the dust, the hair on the bump on the frog on the log, that type of thing. It would be hoped that at the end of four years of botanical studies, of studying only pieces of things, that somewhere you would get the idea or “meaning” of a species or a genus. And yet Goethe would say that the genus and the species do not exist physically, they are supersensible entities, entertained in the soul as an inspiring source of insight. And so you would have appeal to the archetype, to the genus or the species, with capacities other than your intellect in order to get that being which is behind or within the phenomena to speak to you. Hopefully, that's just what would happen after many years of botanical study, you would have to get that being to speak to you to about the meaningful characteristics of its phylum, class, order, family, genus, species etc. Only after a long time of studying pieces could we begin to look more holistically. So regular training starts with bits and pieces of things, and then its hoped that somewhere you'll get the big picture.

Goethe said we should start with the big picture, even though we can't see it with our eyes the way we usually use them, we can see it if we change the way we use our eyes. So his idea of morphology is that you observe a phenomenon and then represent the phenomenon in your consciousness as a picture, and then if you keep repeating the picturing activity over time, that picture will link to something significant that is indicative to its morphogenesis, to its path of becoming, or to what Don Juan would call the lines of the world. This is mystery language which means that everything that comes into existence comes through a particular pathway, and what you're seeing in the form, the gesture and the postures, this is the activity that the life form takes to come into being, to manifest. If you work with this form inwardly, when you represent the image inwardly again and again, eventually your consciousness begins to harmonize with the line of becoming of that thing, and then you see the genus behind the species, and the family behind the genus, and so on and eventually you see what a phenomenologist would call the life gesture.

NM: How does this relate to your work here at Rudolf Steiner College?

DK: Many people that come here to study are disenfranchised by what an alchemist would call the dust, the approach to science and to life that simply has the researcher constantly analyzing data pieces. The people looking for mystery wisdom often are trained in but have a mistrust of the informational paradigm, which puts the basis of proof on the data pieces rather than on the inner soul activity of the observer. Many people who have, say, feelings toward nature, who would want to enter the sciences or something like that, or ecology especially, well, they go and study ecology, and all they learn is the data that proves they can't do anything to help the earth. The data shows them that we really can do nothing about global warming and fossil fuels and acid rain and mercury poisoning and so on, and the data proves it. And so when they go into that type of study they come out feeling like it's hopeless. There is a great despair that arises out of that kind of training.

So at Rudolf Steiner College what we try to do is provide a balance to their natural science work. We work in the natural science area, usually with a phenomenological approach, and at the same time have exercises that we give to strengthen the faculty for picturing, what you could call the imaginative faculty.

NM: The anthroposophical meaning of imagination is the process of taking an idea or a concept and creating a vivid mental picture of how it can be applied in a particular circumstance, so that it may become the motive of a moral deed, and this can be developed to the point where it becomes the faculty of actually perceiving the creative ideas behind the phenomena of nature.

DK: That's right. And the difficulty with imagination is that it has to be made objective. Normally it's totally subjective, it is full of fantasy. And the struggle is to get a person, through exercises to prove themselves wrong about an observation they have made, then their imagination is strengthened.

NM: Could you give me an example?

DK: For instance, we'll be studying weather, and we'll go outside and I'll ask them to observe what's going on, and then we come back later and we make a list of what they feel are the most important aspects of what they just observed. You have the quality of clouds, you have maybe a little wind or no wind, and we make a list of them, and then I'll ask them, “Which one do you think is the strongest from that list?” We have to make some kind of priority, and then they'll decide which they would like to have at the top of the list. And then the next day well go out there, and we'll use that new list as a way of observing, and I'll ask them, “Is there something on the list that you would change?” Well, yeah, yesterday there was no wind and today there's a lot of wind, or today there are no clouds and yesterday there were a lot of clouds, or whatever. And in that process they themselves get to prove themselves wrong, because things have changed. So what's more fundamental or important than clouds and wind is the relationship between them, whereas if it was just data, we would start out with a list of cloud types and names, and the parameters of what's known climatologically about the wind in this season; so many percentage points coming from this direction or this direction etc.,etc. In regular study we would go into the field having all this data and information, and then we'd take it all out in the field to see if anything fit. The answers would all be provided before hand and we would merely be checking to see if what we saw matched what everybody else said we should see.

In the Goethean approach we look first and then form an inner picture and then later make a list of what we thought we saw. Then we go back out and simply observe and represent again and maybe draw a picture to help the imagination in the forming process. Eventually this leads to a condition where out of the thing you are studying itself a question arises such as. What is more primal than wind? What is more primal than clouds?” Goethe was always interested in what was more primal or archetypal in the phenomenon than what was more secondary or derived. Eventually we arrive at a state where we can realize that what is more primal to a cloud type is the relationship which is present between clouds and the shifting of the wind. We start to ask questions about sequence rather than the physics of water vapor in a cloud. We form inner pictures which of themselves link to other inner pictures in meaningful wholes. Yesterday the clouds were in one form and today the form is different. This may seem simplistic to a reductionist scientist but this is a good way to study life. Reductionist techniques work well studying death or pathologies. What Goethe cautioned against when he was living was the science that excluded life from the experiment, that science which is reductionism. So by reductionist empiricism, the focus of your experiment is data, and you prove physical relationships. And you can prove physical relationships mathematically, but you can't prove emotional relationships.

NM: Or ideas like necessity in biology?

DK: Absolutely. Or things like harmony. You can measure it, but you can't really reduce the mood which a harmony creates in your soul into an empirical conclusion. There are things which can be experienced but not proved empirically like the action of a planet upon another planet. In the old days, they would say, there can be action at a distance to explain things like gravity that cannot not be explained physically. Today in quantum physics there is the concept of non locality, it's a similar idea to action at a distance. A classic example of non locality is to split a photon and send one half in one direction and the other half into another direction. At a certain distance place a mirror to change the path of one half of the photon. Quantum mechanics says that the other half of the photon will turn at exactly the same time as the reflected half no matter where it is in the universe. In the physical world this is an impossibility. But in the sub atomic world it is a reality. How can there be non locality? How can we have a split photon reacting in synch to another photon that's half a universe away? Those types of events which require non locality or action at a distance do not show up on the screen of reductionist approaches, but there has to be a way to imagine them, to think them, and so quantum theorists think them but then they have to have something that they can use to prove themselves wrong, and that's an atom-smasher or particle accelerator. If they can make the particle react in the predicted way then they can say, “Yeah,the theory is correct.” The proof makes good science out of theoretical or conjectural science. But as esotericists we have to go one step beyond even physical proof and enter the realm of the soul. When doing experiments in the realm of the soul there will not be particle behavior to prove us wrong, but there may be the feeling of evidence, the feeling that “I Know”. It's at this feeling of I Know engendered without physical evidence that even even phenomenologists balk. Goethe solved this hesitation by being a poet as well as a scientist.

NM: On the other hand, it also seems important that people do go through this empiricist way of studying things. It's a drag if you can see beyond it, but it does seem part of our destiny as human beings to totally explore that realm.

DK: That's true. Empiricism yes, reductionism no. As an empiricist, yes we have to deal with phenomena, even a phenomenologist like Goethe was an empiricist. But an empirical reductionist puts the basis of proof on the physical, causal relationship, and Goethe said that this approach excludes the intuition or the inspiration of the archetype that could be available to us.

NM: Goethe developed this way of thinking, and tried to present it to the world. But it was dropped like a hot potato, because there were much more seductive theories around, like Darwin and Newton.

DK: Well, Goethe was a bit of a curmudgeon, too. According to Goethe, his great contribution was the color theory. And the reason why he thought it was his greatest contribution was because he thought it really did a job on Newton's theory of color and optics, when in fact it really didn't refute Newton's optics. But it did point out a whole other psychological direction for color research which is just today being explored seriously. Newton's color theory was based on experiments he did with the prism, and Newton found that white light was broken up into the spectrum. Newton actually thought that the colors were like particles, and so he had a whole particular theory of color based on a particle of a certain velocity hitting the retina of the eye etc.

Instead of shooting light through a prism Goethe had an experience of spectral colors while he was looking through a prism. He was looking at a portion of the open sky where there was just light. He expected to see colors everywhere but there were no colors coming through the prism, even though it was refracting, and the only place he could see colors was around the edge of the cloud where the cloud was lighter than the sky behind it. He saw a fringe effect, and he thought of a saying of Plato that color comes out of the interaction of light and dark. And so he felt that Newton had made a mistake, and in a way he did, but not in the way that Goethe tried to refute it. Goethe tried to refute Newton optically, and the whole world has gone on with Newton's optics and found spectrographic analysis and such. The whole color industry is supported by what later developed into the wavelength theory out of Newton's particle theory. And so there's all this empirical reductionist stuff that happened in the world arising out of the work of Newton, and Goethe kept saying, but there's a problem with it.

And the problem was that in his experiments with the prism, Goethe looked through the prism, rather than shining the light through it and breaking the spectrum, and what he found was there were two different spectra. There's a warm spectrum and a cold spectrum, and it's only when they overlap that you've got a complete rainbow. And he thought that the idea of two spectra was more primary a phenomenon than the six colors of the rainbow. And where that really comes to the fore in Goethe's color theory is in the last book of the five. The last book is about what he called psychological color, and there, at least for my work, is where Goethe really made his contribution, and there's an awful lot that's come out of that: the Luscher color chip test theory, all kinds of things about psychology of color and the physiology of color that go along the lines that Goethe was developing. And so, for the world, if you go and look up color today in the library, and you can manage to find Goethe mentioned in a book on color, it's usually in the most scathing terms that the scientists view Goethe's work. He wasn't considered scientific, because he was fundamentally at odds with Newton and the dominant paradigm. I've talked with people who were heads of departments in Germanic studies, and who were Goethe scholars, and who had no idea that Goethe did science work.

NM: He's also not considered a philosopher because he wasn't speaking in jargon. He wrote like a normal writer of the time, addressing people who ought to be aware of these things.

DK: That's right. So if you speak about Goethe's science to some scholars, it's kind of laughable.

NM: But Steiner recognized the soundness of Goethe's principles, and out of the depth of his own insight was able to carry on Goethe's work.

DK: Right. But there's a bit of a leap between Goethe and Steiner.

NM: Probably many Goetheanists would disagree that there is any connection.

DK: Oh yeah, and some phenomenologists would have a hard time with what I just said, because they believe that phenomenology is Rudolf Steiner's anthroposophy, but what you learn in phenomenology is to really respect the phenomenon, and then if you can get a sense of the feeling of evidence around the phenomenon, if you build what Steiner called an organ of cognition based on good observation, your task then once that's formed is to look at yourself. And then your own soul activity as an observer becomes the phenomenon that you observe, and that's the second component. The second component is to look at the observer as the focus of the experiment. Goethe even wrote about the observer as the link between the experiment and the phenomenon. The observer brings something to the phenomenon and completes it. That was an alchemical idea that Goethe was familiar with. Paracelsus uses it. Goethe addresses this in the second part of Faust.

NM: Today it's called the Heisenberg Principle.

DK: Right. The classic thought experiment by Heisenberg is that if you can tell where a particle is you can’t tell how fast it is moving at that time and vice versa.

NM: The wave particle duality. In the '80s, I was hearing a lot about this sort of stuff from some of the more popular science people, like David Bohm and Rupert Sheldrake. The holographic paradigm and morphogenetic fields and so on, it was always interesting to me. But it seems that not one of them ever mentions Goethe, who must have been the source of a great deal of their ideas. I can't imagine they were totally ignorant of his work, so it must be a real P.R. problem.

DK: Yeah, because if you hitch your wagon to Goethe, you're in for a rough ride as far as acceptance for a theory. (Laughter) My science is climatology, and planetary motion. I'll talk to climatologists at a conference, and I'll mention Jupiter, and they'll go, “Jupiter?” (Laughter)

NM: I attended a couple of your lectures on weather. As I understood it, you're attempting to apply some of the weather insights of Johannes Kepler, except that now we have enough data to work with, and you're able to demonstrate that weather is affected by the movements of the planets in our solar system.

DK: That's right. Even in Kepler's time, what Kepler inherited was a system of regular, circular orbits. And in his work with Tycho Brahe and the orbit of Mars, Kepler found evidence that the orbits were not circular but they were elliptical. This caused a great foment in him because an ellipse was imperfect, and it was considered that God was perfect and had made the cosmos in a perfect way, and so the orbits had to be perfectly circular. And so what Kepler had to do was shift his picture away from the regular circularity and the Euclidean geometry that was given to him, and start to look at things like acceleration and deceleration, because in an ellipse you don't have a regular velocity or orbit. There are times when it's going faster and times when it's going slower. Kepler found was that when he started to do the math and he was down to minutes and seconds of arc there were portions that were left over, that just didn't fit the idea of a circular orbit, until finally he had a deep conviction that orbits were not quite circular. And this pushed him into the direction of (looking at) momentum, and acceleration and deceleration, that is, the movement of the planet rather than the position. And so in my work what I've found is that it's not so much the position of the planets, but the movement of the planet, the motion in arc, that creates fields of activity, you could say, or that stimulates change in the field. So in phenomenology, the fundamental concept is field, or field properties of things, and everything moving in the field is related to everything else moving in the field, so if I move one thing in the field, then everything else in the field knows, that's the idea. That's an old alchemical idea, you can find it in a hidden way in Paracelsus, and that's what's known today as non locality. The photon at the edge of the universe knows when I move the photon here. So that field concept, that's the Rupert Sheldrake and David Bohm connection, those ideas about field properties they were working with were really alchemical.

So what I've found in my research is that an eclipse generates a field that is harmonic, the idea of harmony is central to the thinking of Kepler. He had a way of looking at angles between planets as harmonic means. Once you move away from regular, circular orbits, you have to move into harmony, because you have wiggle room in the universe. It's not all nice and tight, there's places where things stretch out and things compress. As soon as you get wiggle room, you get stuff overlapping, and as soon as you get overlapping you get overtones and undertones, and the whole field becomes alive.

NM: The regularity becomes more complex.

DK: Yeah, very complex. Absolutely. And so, you need a different model. You need a model that can go along with the complexity, that doesn't try to put anything on the structures as they are, but the type of thinking that can just flow along with the way things are changing. That's what Goethe was talking about. That's his morphology. So in my work I've just done a morphology of watching eclipses for twenty years, and then the data that I have access to, Northern Hemisphere upper air pressure maps every day on the internet, Kepler would have killed for. And so, I've been able to watch eclipses and all kinds of things happen over a period of time, and watch the way the field responds when an eclipse gets triggered by some other planet crossing the longitude of the eclipse or whatever. And so it's a phenomenological approach to very complex, poly rhythmic field activities. But you can model it because of what we have today. We have computers and these maps and things like that. So if you wish to take the time to keep the question open for fifteen or twenty years, you can do the modeling that you need (in order) to keep it open, until the phenomena eventually reveal certain properties. So what I've found over the years is that retrograde motion is very profound, eclipses are very profound, and the field properties of retrograde motion effect things like El Nino. I've done case studies of El Nino, and now I'm working with drought cycles.

NM: I know that most meteorologists and climatologists wouldn't accept this. How are they working?

DK: They usually work from the other side, in a kind of reductionist way, where they take all the pieces of information, and then they feed it into a computer in Virginia the size of two city blocks, that crunches all the data daily, twenty-four hours a day, crunch crunch crunch, and then comes a prognosis is made. But after three days, the decay rate of the average prognosis is fifty-fifty dut to the recursive or iterative nature of the algorithms used to process the data. The recursive process iterates errors as well as hits.

NM: So they can predict up to three days?

DK: Five days accurately, if they're good. But after five days it's considered experimental. I regularly go a month out.

NM: You mean forecasting for a month?

DK: Yeah. And what we predict is trends, so sometimes we get hit in the exact day-to-day category. For instance, maybe a weak storm will come through and put .08 inches of rain or something, and that counts as a rain hit when we have predicted a neutral trend. But if you watch the storm coming in, there's this big, heavy storm in the Gulf of Alaska, and it comes swinging though,and goes up against this high stuck up against the coast (which is the basis for our trend projection), and suddenly the wet storm radically dries out and just a little fringe comes in. In a case like that the trend prediction is accurate but the weather prediction isn't. This is often the case when I have misses. Either that or I just plain overlook something important.

NM: How do the planetary movements come into this?

DK: Fundamentally, if you have an eclipse, and you watch a Northern Hemisphere map, and if you took the position of the moon or the sun on the day of the eclipse and drew a 180 degree line to the opposite longitude, what you would most likely see is that the lows that were along the 180 degree line would deepen on that day, and all the other lows on the chart wouldn't deepen. That was the first insight I got. And then over the years through Kepler, I've been given pictures of what was called the Harmony of the Spheres, where now I use a whole field of lines that go out from that eclipse point, that persist for six months.

NM: Is that what Kepler said?

DK: He said that planetary effects would persist for a couple weeks. But he didn't have an eclipse grid or daily fax maps of the upper atmosphere.

NM: He didn't have the data.

DK: Right. I have a satellite eyeball (Laughter), and (I can see that the effects) persist for a lot longer than a few weeks. And so, when another planet crosses that eclipse point, those lines of the harmonic field get very excited, and then (if there happens to be a low transiting one of those lines in actual space, and it's on that line when that planet hits on that day, then that low will deepen radically. So fundamentally the lows are wandering, until some motion in arc event triggers one of the lines of the eclipse grid and suddenly all the lows that are on those lines deepen because Mars just went across the eclipse line or Jupiter went across the eclipse line.

NM: And can you determine any difference in the character of the effect whether it was Mars or Jupiter?

DK: It's subtle. Jupiter has a tendency to support blocking, and Mars has a tendency to be aggressive rhythmically.

NM: So there is a relationship to the different qualities traditionally associated with the planetary bodies?

DK: Yeah. But it's my experience that responses have to do more with their rhythmic movements than their position. For instance, Mars has a certain motion in arc, it's often moving a degree in arc of longitude every day, or a degree every two days. Mars crossing a point is just a blink in time and it is constantly changing. When Mars is active on the grid the weather is constantly changing. Whereas when Jupiter crosses a point it's on there for a week. That rhythm tends to suppport high pressure areas that remain stationary and block the jet stream. If Pluto crosses the point, it's there for months. That influence tends to be obliterated by faster moving planets.

NM: So how do you bring your work with the weather to the world?

DK: We have a weather service called Climatrends (climatrends.com) that provides forecasts for wine growers in Sonoma County.

NM: And you've been forecasting weather more accurately than your average weather bureau?

DK: I can forecast long term trending patterns more accurately. The weather service does very well with three day forecasts. Any prediction under five days is for weather, any prediction for anything over that is for trends. Six months ago I predicted that there would be a very strong dry period this year (2000-2001). Well, here we are in January and way below the average for rainfall, and the only time we got any rain so far this year was when Mars was transiting the end of a series of lines out over the western Pacific. As soon as Mars hit a particular harmonic point it started raining, and then Mars went through and moved out of harmonic range and it stopped raining.This was in October. I also predicted we would have rain in October, which is pretty unusual, and that's what happened. I predicted storms in England this fall, and that's what happened this year.

NM: How do people respond to this?

DK: The ones that see it work say, “Well, this is really cool.”

NM: Do they accept your methodology, of looking at the planets?

DK: I try to explain it to them, but most people just kind of glaze over.

NM: People in weather?

DK: Yeah, because if you mention Jupiter, immediately you're a flake.

NM: They'll maybe accept the moon?

DK: Maybe. In the books it's called an “obscure influence.” Moon and sun are classified as obscure influences on the weather! (Laughter) Sunspots have been studied. But the problem with the way they've been studied is if you think that sunspots move the weather, then you tend to think that sunspots are the only thing that changes the weather. But being a Goetheanist, I have to say the whole field is influenced in all parts. That means that to really model climate trends all planets have to be factored into the mix. When a planet moves, the whole field knows it, and so the way in which the field has to be structured and the way the experiment has to be modeled are exactly opposite to pointing out one element and gathering data on that one element, which is the reductionist approach.

The problem of the whole modeling procedure has been really crazy for me, because every motion of every planet every day has to be factored in, and that can be a daunting thing, but if you're working Goetheanistically, keeping all the questions open, then over the years patterns emerge which lead to insights about modeling techniques. Through decades of research my charts have gone through totally radical revisions, but it's finally at a spot where I can get out of the way, and let the model interact with the phenomena.

NM: Could we talk a little more about Goethe's work with plants and animals?

DK: Sure. Goethe became interested in plants through the work of Linnaeus, who was the person who developed the binomial taxonomy that we have today: phylum, class, order, family, genus, species. Linnaeus developed this taxonomy studying the sexual apparatus of plants, counting stamens and pistils and whatever, mostly of trees. And the annual plants were not a part of his work. He studied different species of trees and the flower parts of trees, and then based his taxonomy on that. Goethe, as a young man, read Linnaeus and had it in his pocket when he went AWOL in Rome. Under cover of night and using a pseudonym he had left the court in Weimar, Germany, because he couldn't stand working as the Minister of Mines and Sanitation anymore and he couldn't stand court life any more, so he left and went to Rome, traveling incognito. In his pocket he had Linnaeus. And so he was studying Linnaeal taxonomy as a way of trying to understand plants, and he was in a botanical garden in Palermo. There he saw a plant called the mother of thousands, it's a succulent, in which the leaves form little plantlets on their tips. Through this plant he could see that the leaf was a flower. Suddenly in his mind he saw the archetypal relationship between the leaf of any plant and the flower of any plant. He saw that any flower part on any plant was really a modified leaf. This was the way which Goethe understood the field properties of all the different plants, they all have the leaf in common. So when he had his Proteus, he started studying the way in which the leaf forms in any plant transform into the flowering processes in that plant. This work he called the metamorphosis of plants, and he found that in many instances in a given species the calyx leaf would transform into a corolla, or a corolla would transform into a stamen. He found that these things which in regular botany were reduced to separate parts were in reality linked through the field properties of leaves.

In his essay the Metamorphosis of Plants, he showed that in many plants the leaf was the thing that was consistent in form with all of the other modifications. This leaf was the focus of the field properties of a plant, and everything else that appeared to be different changes were really metamorphosed leaves. That's his contribution.

You can find certain textbooks that were written that way in the late 1800's, and then that way of thinking in wholeness went out of favor and turned towards reductionism. But now what's happening is, there are a few brave botanists who are coming back and starting to bring those ideas back in, because they find that if they look at botanical metamorphosis in that way, it's much clearer to the students.

NM: What replaced Goetheanism?

DK: Reductionism. This part has a name, and this part of the part has another name etc. But some researchers are using more phenomenological methods.

NM: Who are these brave botanists?

DK: I'm not heavily into systematic botany, but my students show me certain botanical texts that have flavors of morphology. Also there are phenomenological scientists influenced by anthroposophical ideas. Craig Holdredge of the Nature Institute, is doing nice things along these lines.

NM: So how has this work been extended by people?

DK: A lot of work in anthroposophical circles has to do with what Rudolf Steiner would call the etheric realm, which is what in regular science would be called field properties. Steiner's picture of this was in line with Goethe's thinking on the morphological fields, and that's in line with the thinking that goes back to the alchemists. It's the idea that we all are participating in the field directly with the archetypes, Steiner took these ideas and applied them in medical work, agricultural preparations made for manure, a lot of healing work, massage work. I've been told stories about people who do this work, some lady broke her leg, and a masseuse gave her an etheric massage over the cast, she didn't touch the broken leg at all, and the attendant doctor who didn't know this was happening was amazed at the healing process, because this lady was actually working outside the cast and didn't touch any of the tissues, but could affect the healing process in a dramatic way. Which is sort of standard stuff for these healers, but if you go to a regular AMA person they're going to say that's bogus, it can't be done. So there are a lot of things that, quote, “can't be done”, but are being done pretty much regularly, like homeopathy, which regular science can't recognize.

NM: They say it's a placebo.

DK: And I say, what's placebo? I mean, that's not an answer. That's an admission that we don't know. So, if we really go into the placebo effect, why does placebo work? We could ask that question back, and that points to the field properties, to activity of forces in the soul and forces in the world where we can bring certain things together in time, where certain things would happen in a certain time frame that couldn't happen in any other time frame. For instance, there are studies that were done by Lily Kolisko, who was a doctor during Steiner's time working on the activities of metallic alloys during particular planetary alignments.

What was happening was that in munitions plants, there were certain batches of shells that would blow up in the guns, because the brass casings would rupture on the shells. This was because the metals in the casings wouldn't have alloyed, there would be flaws in the alloy. So they went to Dr. Kolisko, and said, “You work with with metals. Can you look at this?” So she took a look at the records from the factory, and she found out that the flaws occurred on the days when the smelter was operating when there was an adverse relationship between Jupiter and Venus. Jupiter is associated with tin and Venus is associated with copper, and together they make the alloy brass. And when there were adverse conditions between these two planets the metals would not alloy properly.

NM: Squares and oppositions?

DK: Right, So she went to the factory, and said, “Avoid these days in the future, and the problem was gone”. And that is what happened. There are many of stories, and it's those types of things that if you asked a regular scientist what was going on, they would say, “Well, it's something in the molecular properties of the metal, or it's a “coincidence” or my favorite “You were lucky, do it again”. (laughter) Some scientists can believe in luck but not in planetary influences.

NM: From anthroposophy, I understand the etheric realm to be concerned with the natural properties of growth, metamorphosis, and reproduction. It's a new association for me to consider field properties in conjunction with the etheric world.

DK: Well, in that realm which Steiner called the etheric, there are activities and forces and beings, you could say, archetypes, that give movement to, or animate, the forces of nature. In the ancient world, they looked into natural phenomena and saw that they were ordered and they thought that this must be the work of the elemental beings or something like that, etheric beings. It was always understood that there were patterns that were ordered and repeatable, that seemed to have a kind of intelligent focus to them, and the intelligence and repeatability of the pattern gave this force a kind of persona, a beingness. And so there would be one persona for rain and another persona for wind and another persona for light. Nature was filled with repeatable patterns, which occurred only when certain other things happened, so there was intelligence behind them. They were not random.

These qualities could also be recognized in human being as elements of personality. So in the nature world, those etheric forces in nature were considered to be spirits. And today, we look on them just as forces, but as you work with this work, and start to have these experiences—like Jupiter and Venus in their particular configuration creating difficulties in the alloying of metals—you begin to have the experience that Jupiter and Venus also have personalities, that they have affinities, that there is intelligence behind them. We can get the distinct impression that the whole field of the atmosphere is activated by their presence and their movements which, seen from this perspective, are a kind of breathing. And that is a very different vision, inwardly, than simply seeing atmospheric forces interacting in pressure gradients.

NM: Or seeing the planets as hunks of stone or balls of gas.

DK: Right, so in physics you have the billiard ball kind of reasoning—you know, this hits that that then hits something else—but they never say anything about the original hitter. And so, who's the hitter? The primum mobile? The prime mover, the one who instigates the movement that leads to the first hit? Kepler was very clear: It's God. And a lot of Kepler's work was not valued as a result of this belief. Some scholars think that Kepler was kind of a sleepwalker, and that he found his laws of planetary motion kind of accidentally, like a naive person or a mystic.

NM: An idiot savant.

DK: Yeah. Because he didn't arrive at things in a causal way. He arrived at them in a teleological way, and yet here we are with Kepler's laws of planetary motion being the basis for putting spacecraft into orbit. So the question really for the future as I understand it is: Can we allow a teleological reasoning process into the study of field properties? If we do, then quarks become the personae of beings. There is an intelligence behind the way they work, and as we start to work with them and see their interaction, we may start to perceive that the whole field is intelligent (this is the holofield of David Bohm), every quark is listening to every gluon, and every gluon is listening to every meson, and out of that harmony comes the great intelligence of the cosmos that we participate in. And I feel that's what people are yearning for, a cosmology that can support a different worldview.

There's an awful lot of return to the goddess energy today, people looking for a different way to relate spiritually to nature, and while I value the sentiments, in many instances, I think the inertia is a retromove, because people are moving in a direction of the techniques that worked in the past, and bringing them forward as if they were new. This is a common criticism of my weather work simply because it has a relationship to astrology. And, truth be told, scientists are rightfully wary of anything that smacks of subjective perception rather than scientific thinking.

It's my understanding that at the end of millennia, that everything that worked for the last millennium is brought forward for review, and only the real seed like things are going to go into the future, but everything has to come back for a review. So we're living in a time now, in 2001, when everything is coming back for a review. You can go to Barnes and Noble and find books on Aleister Crowley's chicken ritual or something, that not too long ago you'd have to have the “authorities” after you if you had that book. So that means everything's available, and in that context where everything's available what do you use as the litmus when your quarks start to be beings? What's the litmus? The litmus, I feel, has to do with how you practice looking into your own soul. In the ancient world, or in the alchemical world view, it was considered that a person who made a medicine projected their moral profile into the medicine. It was understood that there was something of the morality of the pharmacist that went into the preparation of the medicine. That which went into the medicine was the will or the intention of the operator.

NM: Similarly, the love of the doctor.

DK: Right. Bedside manner, absolutely. Now we get the placebo. Now if the placebo works, why don't we work with it? Why don't we make it into something? That something would be radical bedside manner. This would mean that we would have to educate physicians not to be pathologists, but to be healers. But there's danger, because, in the healer, if it's magnetic or what we today would call touchy-feely, then whatever is yucky in the soul of the healer gets transferred to the soul of the sick person even when they are cured. They get cured but not healed.

So once again, you can't just go back to the old practices simply because they worked before or even because they may work now. They worked before because of the human relationship to the archetypal field properties of things, and the intelligence of the cosmos, and the beings that are living in the archetypes. They worked because the operators would strive to get their consciousnesses in line with these properties of the beings of the creative hierarchies which stand behind the manifestations of nature,the substances which they wished to transform. The work they did on themselves gave their protocol for healing the proper mood of reverence in order for it to be a healing and not just a cure. A healing includes a change of heart in the patient so that they don't get sick again, a cure does not.

So, in the work here in Goethean Studies, we try to get the people seeing that it's how they live their life inside their soul that determines the quality that comes out into their work in the world, and that these fields of activity are reciprocal to each other. That what you do in your inner life is reflected in what happens outside, and what you do outside is a reflection on your inner work This reciprocation is what we call soul breathing. Most of the year in Goethen studies is spent talking about soul breathing as a technique, as a way of training yourself to really see clearly this moral relationship between yourself and the world. It's the door into this new science.

Reductionism is reaching a limit in the smallness of the reduction. I read where the limits of nanotechnology will soon be reached because the quantum effects of smallness will soon limit how small a circuit we can make in a computer processor. The search for new particles is just about over because all of the particles which the physicists thought they would find have been found. And where are we?

NM: We're stuck with just particles.

DK: We're still with the particles. But once we move from particles to being, I feel that's the next paradigm shift. It has to move in the direction of morality. What's the morality of the researcher? That's scary. No one wants to go there. But we're going to. (Laughter) We're all being dragged kicking and screaming into questions of the good. And the new age people are calling for that because they say this is what has to come, and I agree 100%. But the techniques used to get there need to be cognitively creative and not simply repetitive of old methods.

NM: It can't just be an archaic revival. There has to be a new way of working that takes our present-day vantage into consideration. As we became more immersed in matter, a more primordial understanding was supplanted by the intellect for a reason. Western development was not a mistake or a wrong direction, but a necessary separation from the old, atavistic, intuitive understanding, so that we would be equipped to find it again in freedom.

DK: Freedom is the key word. So now we have the freedom to trash the planet, and that's happening even as we speak. The hierarchies that are watching us do this don't understand why we would want to do it. They have created nature in the image of the Creator. And we're made in the image of the Creator, but in our inner planes we have freedom to go against the creation. And so there's been an evolution of that principle of what was given from the Creator. It has been carried through the sacrifice of the Son towards the unfolding of the Holy Spirit. I guess that's the way Kepler would say it. And that movement means that humans now are free to not go along with the comos. However, it would be prudent to turn our souls consciously towards the good. The first paradigm was beauty; now we've lived through the paradigm where the question was “Is it the truth?” I think that the next great question will be “Is it Good?”.

Dennis Klocek

Dennis Klocek, MFA, is co-founder of the Coros Institute, an internationally renowned lecturer, and teacher. He is the author of nine books, including the newly released Colors of the Soul; Esoteric Physiology and also Sacred Agriculture: The Alchemy of Biodynamics. He regularly shares his alchemical, spiritual, and scientific insights at soilsoulandspirit.com.

Similar Writings

Earth Consciousness

The picture is an image of stars falling out of the sky as snow and then falling to earth as crystals. From the point of view of alchemy my thinking is creative when it is focused on the cosmic or starry dimension of my life. That is the source of solutions to my issues. Alchemically,…

Silica and Clay Polarity

Silica is the light pole in the minerals. It is a kind of flowering process in the mineral realm since silica in plant growth enhances the refined properties that light brings to plants. Photosynthesis requires light for its action. The light interacts with the flavonoids (phenols and tannins) and anthocyanins (blue and red pigments that…