Esoteric steps toward self-renewal

By Dennis Klocek 28 min read

[Ed: This was the first lecture of a series given by Dennis in 2002, but we only have this one transcription. It has been edited to be a stand alone. For a complete series like this, please see The Heart, Warmth and Karma: Integrating Steiner’s Spiritual Practices into Modern Healing, The Healing Power of Symbols, and Chronic Pain & Esoteric Initiation.]

Introduction

What I’d like to do here is share a series of exercises. I’ll try to explain a little of the physiology of how they work, maybe touch on the psychology, and place them in the context of what we could call an alchemical practice.

Hopefully, by the end you will have some seeds of a way of approaching stress management, or even pain management, in your own life, in a way that’s productive. So that if you do need other things, other medications or whatever, you don’t need them quite as much.

The Two Forces in the Soul: Sympathy and Antipathy

There are certain principles involved with this work, and I’ll explain them in an alchemical way so that we can hopefully understand the processes involved.

I have found over the years that these very basic ideas go far. They show up throughout Rudolf Steiner’s work and throughout the medical work out of Anthroposophy and healing work. You find these ideas in many places.

What I’d like to do is share some of the fundamental pictures so that if you want to go out and do research, you have something to work with.

Stress indicates that something that is naturally in a reciprocation is either stuck or is on too much. In the human soul there are two forces. One is sympathy and the other is antipathy.

Sympathy and Sulfur

Sympathy is the force we have in our blood. And in the soul, the force of sympathy is the ability to unite in an intimate way with something else for the purpose of allowing the world to enter us.

When you take on something else, you kind of lose yourself a little bit and you take on the other. That’s sympathy.

In physiology, this is the role of the blood. The blood is there to touch all cells, all organs, all systems, touching and saying: Okay, we can help you. You go over here, and you go over there. Take this from here to there. Keep the rhythm flowing. Keep everybody happy.

The force in us of the blood, living in this sympathetic blood, is one of the most fundamental poles in the soul. And an alchemist would say that it has to do with what is known as sulfur.

It has to do with things that are separate becoming more intimate. You make a compound out of two elements: that’s sulfur. I take two disparate things—carrot and potato—put them in a cook-pot, and end up with soup. That’s sulfur.

The function of the blood is to carry the impulses of sulfur, the impulses of sympathy. And what it does, it keeps saying: That’s okay, move this along, go over here, put this here, I love you, don’t worry about that. That’s sympathy.

But if sympathy gets out of balance, it says: Whatever, give it to me, I’ll take it on, I’ll just keep taking it on. So the blood keeps taking on pastrami sandwiches at 11:30 at night, stuff like that. Eventually the blood goes: Aaaahhh, I can’t deal with this anymore.

When that happens, the whole soul’s mood shifts to the opposite pole, and that’s antipathy.

Antipathy and Salt

Antipathy is the separation of two things that used to be united. Just the opposite gesture.

In sympathy, I have two things that are separate that I’m working to bring together. In antipathy, I have one thing that breaks into two pieces.

The gesture of antipathy is what an alchemist would call salt. This is sulfur here, this is salt. And that’s really a function of the nerve.

Neurology in the human system is salt. It says: Here’s an impulse coming in. It’s such and such cycles per second. It’s light and then dark and then light and then dark. And that’s our sensation.

I don’t get “there is a building, there is a tree, there is a person.” That’s salt.

All of my senses are built out of a force of antipathy. My skin says antipathy: Here’s my skin; there’s Richard’s skin. Antipathetic. Your skin is not my skin.

All sense organs are built of skin, and scar tissue. The lens of the eye—scar tissue. Whatever it is: this is mine, this is yours. That’s salt.

And it’s the neurology that carries the forces of salt. Layer after layer after layer after layer of silica in the nerves: salt. Here, not there. Salt.

I get an impulse in my eye, and suddenly it’s in the back of my brain. Here, not there. It’s either here in my eye or in my brain. It’s not kind of somewhere sloshing around in the blood. It’s either here or there. Where is it? I can measure it. It’s either here or there.

All of that—measurable, quantifiable—is what we call nerve, salt, antipathy.

The Oscillation of Soul

And the soul oscillates between antipathy and sympathy, salt and sulfur, to try and get balance in the soul life. There’s a stimulus and a response and suddenly I’m in sulfur or salt.

I have to find some way in my life to get those two to balance. If I don’t, that’s stress.

I have a superabundance of one, due to a temperamental disposition or a characterological disposition, or my spleen is out or something and I can’t process. Then another part of the system has to kick in with an abundance of the opposite in order to try to bring a balance.

And when that happens, I’m not all I could be in the moment. I’m reaching down into the bag for some energy that I may not have.

If they’re all working tick-tock, and Peter and Paul are happy and they know what’s going on, then I have abundant energy. That’s when stress is good.

When I have abundant energy and sympathy and antipathy in the soul are balanced, then stress makes sympathy and antipathy vibrate to a higher level. Suddenly I’m functioning at a higher level, I’m having a really good time, stress comes, I can meet it, I have energy to meet the problem, and I go and do it. Stress is good.

When stress comes and I’m in a lop-sided stage, and I reach down to try to get some energy and I can’t, then that may be the onset of a disease. The straw that breaks the camel’s back.

Mercury: The Healer in Rhythm

So the picture is that the organism wants the balance. We need to supply the balance in order for the organism to get what it needs, so that when stress comes we can use it to get to the next level.

That’s easier said than done. Because the great task in this is: Know thyself. Nothing in excess.

The great mystery challenge: know thyself, nothing in excess.

That’s the call to what we call practice. To do inner work.

And inner work involves somehow getting this blood and nerve to relate to one another in a rhythmic way. When they relate to each other in a rhythmic way, the rhythm creates an abundance of available energy. In the mysteries this is called mercury, the healer.

And then the rhythm of the practice allows the antipathy and sympathy to be balanced. So stress comes, the mercury lifts the rhythm to a higher level, and suddenly I’m learning a lot from what would normally be a very dissatisfying experience.

That’s mercury. That’s integrated. That’s energizing. Mercury.

Mercury and Rhythm

The other name for mercury is rhythm. And if the blood and the nerve are the two polarities, mercury is the whole rhythmic structure of the blood and the nerve.

So it’s the rhythm of my sensation during the day, whether that’s rhythmic or not. If my choice of music is [rough heavy metal/rap impression], then maybe it’s not so rhythmic. So you need to look at that.

And if every time something happens my response is: Oh, yeah, I’ll do that, that’s okay, I know nobody else wants to do it but I’ll do it—then over time, over time, over time, I’m going to say: I’ll do that, but you’re going to pay.

Then you get pretty nervy. It’s even in our language: I’m stressed, that’s why I’m nervy.

So the prophylactic for this is that some kind of capacity needs to be developed in the soul life so that there is an abundance of rhythmic forces available at your disposal. A reservoir of rhythmic forces.

It’s like your ATM. You’re in some weird country, you go whsshh, and then it tells you how much your bank account has in it six thousand miles away. We need that.

So that bank account, that ATM, is the practice. Because a practice is doing the same thing in time over a long time. And that means that the rhythms in a person’s life somehow come under, if not their control, at least their scrutiny.

We’re actually learning how to live and swim in the rhythmic element with a practice, to observe the imbalances of sympathy and antipathy as they arise. That’s really the purpose of an esoteric practice.

And over time, that builds the capacity to say: Here’s a particular pathology that I have that has a superabundance of sympathy for three hours until I flip into antipathy, and I notice the pattern again and again. My friends tell me about it, but I can’t hear it from them, because it stirs up too much antipathy. But if I see it myself, in the beginning there’s an abundance of self-antipathy towards it.

That’s called meeting the Guardian of the Threshold in Rudolf Steiner’s language. And there’s a teaching there about that antipathy, so that you can learn to integrate it into more of a mercury stage.

That happens by watching the antipathy arise and saying: Thank you for sharing, please sit down.

And the antipathy says: Okay boss, just trying to get a little energy from you, and I’ll go sit down but I’ll be back. And it sits down now, and what comes into the soul is sympathy related to antipathy, mercury, empathy, and compassion.

Then you can be in the tough spot. You can be in a weird spot. People can be coming at you, but you can reach back in and say: You know, I hear you, but I can’t really go there with you right now. I’ll listen, but I can’t go there.

And that balance is these two coming together. The nerve and the blood speak to one another, suddenly mercury comes out of it, and then you don’t have to do it, you just have to be there. That’s all. That’s getting it.

So practice cultivates that rhythm between the nerve and the blood so that eventually mercury can come up. It doesn’t mean you always have the answer. It doesn’t mean you always win. But it means you’re always a player, and that’s what I’m talking about.

The Peace (Rest) Exercise

So there’s a practice, that in the Consciousness Studies course we have as a root. I call it the Peace exercise. Rudolf Steiner calls it the Rest exercise, you could call it the Ruhe exercise in German, rest. You could call it the L exercise. You could call it a lot of names, but fundamentally here is the picture.

When I experience something that is counter to the way I think it should be, I’m going along and I’m sort of rhythmic. I’m pulling out in traffic and some guy guns his engine to make a light that’s a hundred yards beyond where I’m coming out. And I’m late too.

He makes me slow down my impulse, and suddenly, I have something that’s been grooving and it gets checked. From my observation, this is the single greatest stressor. I have something going and you get in my way.

However we play that scenario—something comes up where my inertia gets thwarted. And there’s energy that can’t go somewhere. That gets put in the doggie bag. And the doggie bag has very dark things in it.

So for five minutes we’re nailing this guy in our head, thinking bad thoughts. That’s stress.

But the check in inertia, when we begin to cycle beyond the event, that’s where stress happens. You finally got your doctoral thesis finished, and you hand it in to the committee, and the guy who’s the head of the review committee recognizes your name as the guy who stole his girlfriend two years ago. And suddenly you’ve got some problems.

However it is, you’ve got something going that you think is very cool, and something stops it. And right then there’s an overburden of energy and you have to take that energy and stuff it.

When you put it in the bag, the bag gets bigger, and eventually the bag will pull us into an imbalanced cycle of sympathy or antipathy. Maybe you become overly sympathetic. Maybe you become overly antipathetic and start reaching for the .38 under the seat. However it is for you, that scenario creates a situation where you have to do something with that energy.

It’s not just going to go away, because it was already designated to do something you thought was very cool. Your whole system is filled with it. And then you’re left thinking: What am I going to do with this? Okay, I’ll stuff it, put it in the bag.

If the bag just keeps going, with no way to deal with it, then that lodges in the heart or the liver or somewhere else. And then it becomes a pathology.

So in order to deal with that, you have to have presence in that situation to say: Okay, here we go, I’m going to reach into my practice bag. I’m going to pull out enough energy to match this inertia thing. I’m going to put them together and watch them go mano a mano with each other. And somehow they come out into neutral space. And then I can submit my thesis to another institution, or take it back and make it better, and I’m not really carrying the energetic burden.

That’s the ideal. The practice gives you something to neutralize the energetic overburden of inertia.

Two Components of the Peace Exercise

In the Peace exercise there are actually two components.

The first is that you designate that the content of your consciousness is going to be occupied by some thought. That’s the first part. Instead of a random thought, I’m going to determine the content of consciousness. Rudolf Steiner calls it Rest, Ruhe, whatever. Some people don’t like that word, so we call it Peace in Goethean Studies.

The content doesn’t really matter. What matters is that you determine the content.

Then you use that content—a word or a picture—and you use the will, the blood, the will-force, to grab that word. Instead of just getting jammed and either eating it or getting aggressive, you use the will to take that picture or that word and start to work with it.

The will, instead of being like whatever, suddenly has a designated purpose esoterically. And you say to yourself: Peace.

And then you watch. You’re cool for about five and a half seconds, and then okay, the junk comes back again. So you repeat it again: Peace. Five and a half seconds without junk. Wow.

You can usually repeat this about four times before you start thinking about something else. Because now, not only are you pissed, you’re bored.

If the triggering event was a real inertia-stopper, boredom leads you into into self-reproach or revenge. If it’s sympathy, you’re a bad person. If it’s antipathy, it’s revenge: he’s a jerk.

So instead of giving sympathy and antipathy the attention, we want to find something in the center, in the mercury sphere, that we can use to create a rhythmic will-impulse to absorb that inertia.

That’s the practice. I say Peace, and I watch the peace go from salt—the word Peace—to sulfur. I’m no longer just saying peace (salt). Peace has been said, and then the saying of the word has moved to sulfur—an expanded consciousness of silence.

The impulse to say Peace, or to think Peace, has become something ineffable. Going from salt to sulfur.

In that sulfur stage, there’s just a little bit of breathing, and that’s just what we want. And then salt returns in the form of the idea that I have to do something, or think something, or text someone.

So the task is to sustain my sulfur Peace. When I do, I get a little breathing space. And then through rhythm sulfur once again becomes salt, and once again the chattering monkey of Zen practice comes in: That guy cut me off!—Peace.

Ahh yes, sulfur. Space. Breathing.

Salt: I don’t like it when people cut me off!

Peace. Sulfur. Space. Silence.

Salt: Damn.

The movement between the two is the action of Mercury.

If you establish this rhythm consciously, it’ll take about five minutes of: I’m going to put Peace here. I’m going to put Peace here again. I’m going to put Peace here again. It gets a bit silly and frustrating, but someday the effort to hold one specific thought blossoms into a perceptible rhythm of the mercury sphere.

The rhythmic mercury of the practice takes your will, and the blood and the nerve can get behind it and say: Oh, I see, we’re not going to do crazy things now. We’re going to do the practice. Oh cool, yeah, I’m just working on myself.

And every time you work on yourself it’s like somebody telling you your stock just went up. It’s like Christmas. Because you know what you’re getting? Free forces. Free energy.

You free energy up from the burden of griefs, disappointments, angers, and most of all, expectations. Free energy begins to trickle out of the effort to establish a practice.

You can determine the content of it, because you just did—by focusing only on one thought.

But as soon as you’re so full of clean energy, all the wet, soul nasties and things that go bump in the night come creeping in and tell you that you ought to be doing something else.

So you designate the thought again. Then the power of the will in the rhythm of mercury helps shift the energy. Suddenly instead of having to jam your feelings into the doggie bag of your soul, your practice becomes capacity.

It becomes usable to fight your battles. You may even get insight out of it. At the very least, you’re not looking for the .38 under the seat to go get the guy who checked your inertia. At least you’re not just jamming it and saying: I’m a bad person—because that can go on for days.

We don’t want days in the barrel of resentment. Hours maybe. But not days.

The practice won’t obliterate the need for incidents like that. Rudolf Steiner himself—imagine, he’s communing with the Hierarchies, and someone comes up: Dr. Steiner, we need a decision about building codes at the Goetheanum. Everybody has their stuff to deal with.

But the mercury sphere is the only place where we can get some purchase on the peaceful and effective way forward. And to do that we need to establish a practice where we designate our consciousness to be in a particular place for a particular time.

Extending Silence

There are two parts to this. Suppose I say Peace, or Rest. I say Rest. And then it comes back. Rest.

Then I can experience the silence after the word goes. And it is good, and I want to extend that silence.

There’s a technique for trying to extend the silence. It is best to do this every morning.

Over time you notice the silence after the word is different than other daily qualities of attention. It is a pregnant silence. What you’re actually hearing in that silence is that as the word goes out, something else is coming in.

And what is coming in is actual rest, actual peace. Actual forces of abundance that you don’t cognize because they are silent, because they are peaceful.

What you’ve done with your practice is ask for a grant. Your attention going out is the grant proposal. And the law is: what your attention is, that’s what it meets out there, and that’s what comes back.

The alchemists say: what goes around comes around.

So if you designate consciousness toward Rest or Peace, that goes out from you as a principle. It starts to create a resonant cavity in the space around you. Rudolf Steiner calls this the “hut.”

That space becomes resonant with the thing you are trying to establish. It becomes harmonic with the thought you are designating. And that begins to come back to you in the silence after you let go.

You may find, over time, suddenly: Wow. I’m getting some peace here. I’m getting some rest.

The rule is: where you focus your attention, the universe says: Okay, we’ll put energy there.

If it’s twenty minutes of bad thoughts about the guy who drove past, then that’s what gets developed. That’s the law of humanity. We are incredibly efficient designators of attention.

Every adversarial being knows that. The only beings that don’t know that are us.

Linking Inner Work with the World

So that’s the first part of the work. We could call it inner practice, where the task is to try to control the forces in my own organism.

The other component in this work is a very strong Rosicrucian element that is not quite so present in Anthroposophy. The cognitive side—Philosophy of Freedom, and all of that—is strongly developed in Anthroposophy.

What’s not really developed is the relationship of my inner work practice to the sense world. And that’s really a Rosicrucian gesture.

It is possible to develop an inner practice in which you purposely link your cognitive experiences in spirit to your sensory experience in the world, to what you do for a living.

Rudolf Steiner calls that the New Jerusalem, the school of Michael.

So now we bring this experience of ourselves as consciously thinking beings into rhythmic contact with our experience of ourselves as beings of sensation. We bring these two together in a new way, and a new force comes up in us. That newness, that’s the “new” part of the New Jerusalem.

It means disenchanting the world from being just stuff. We get to participate in the world with a consciousness that is spiritual and practical at the same time.

The scholar Owen Barfield calls this the new participatory consciousness.

The old participatory consciousness was: God tells you what to do, you design a ritual to do it, and you get the juice. That’s the older pattern of esoteric training. Still active today.

Then came the non-participatory consciousness. That’s modern physics, the AMA, Enron, all the political and intellectual edifice that says: I’m not going to participate in the original creation. I’m building empires and financial fortresses. That’s the hubris of non-participatory consciousness. We’re all familiar with the fruits of that one, and it is now showing its vulnerable underbelly.

The new evolution of these two older forms is the new participatory consciousness, where we consciously go back into creation—but this time as co-creators with the Hierarchies, as servants of the Word, the creative Logos.

This is the school of Michael. This is the outreach end of Anthroposophical work. Through the practical life, out into the world, is the Rosicrucian stream in Anthroposophy.

So that requires that we take the same type of inner work we’re doing in our own soul and find an analog for doing that with sense objects.

The sense object we’ll use here is your pen. And then, with a leaf, the comparison will be how sensation from a pen and a leaf change our inner gestalt, how they make us different soul-wise.

The truth is, the impact of the world is happening in us all the time, outside of our control—unless we establish a practice to meet it. Colors, smells, tastes, sensory impressions are continually impacting our organism and creating the content of our consciousness.

Much creative energy is dissipated in that process. If we were to retain just a bit of it, we could have it as a practice that unites inner and outer life in a new kind of seeing, hearing, touching.

Salt and Sulfur in Sensation

The practice is very similar to the one I described with sympathy and antipathy.

On the inner plane, you have an impulse, and then it goes away from you and comes back. That rhythm is one breath.

In sensation, the gesture is the same, but the poles are reversed. When I look at a lamp and say “lamp,” that’s salt. It’s there, outside.

But then the image forms inside me and begins to morph. That’s sulfur.

So in sensation, I’m sure: That’s a blackboard. Salt. But then my mental image of it is less real. That’s sulfur.

In the opposite condition, if I have a thought, that thought is real to me inside. But when it starts to drift, it becomes sulfur—less real.

So there’s a kind of dual breathing: outward into the world (salt) which dissolves into inner image (sulfur), and inward into thought (salt) which dissolves outward (sulfur).

Rudolf Steiner said: mental images based on sense impressions go into our soul and have liaisons and trysts there, propagate, have families and beer parties and fights—all at the expense of the equilibrium of our soul life.

They slide below the radar, do their business, then come back and tell us: This is who you are, man. And we go: Oh yeah, that’s who I am. Maybe not. They’ve just created something out of their own designs.

The task is to hold the salt and sulfur rhythm consciously, not let it drift unconsciously into associations.

The Heart Eye

The two poles of these practices—inner work and sense work—together form what we could call the development of the heart eye.

So the other side of the inner work done inside yourself is the inner work that engages the outer world.

In Goethean practice, you have the fixed gaze and the open gaze.

In the fixed gaze you say: There’s my pen. It’s real, it’s out there. And then you look at it in such a way that you feel you’re drawing it inside, representing it inwardly. You try to feel that the inner picture has something to do with the outer thing you just saw.

At first it can be frustrating. Like trying to push a wheelbarrow with no wheel. Nothing shows up.

Here’s the secret: the inner image is not the same kind of image as the outer one. It’s a field-seeing. An as-if.

Artists, trained to breathe things in, often see visuals. Musicians may get melody lines. A cook may experience tastes or smells. An engineer might see plugs and sockets.

It’s all valid. The task is simply to breathe in the thing, reflect it up, and feel: Do I have the same kind of feeling inside as when I’m looking outside?

Practice that, and one day the image shows up in some part of your body—your lung, your throat, your kidney—and suddenly: technicolor, movies, archives, the works. You were maybe just looking in the wrong place.

Behind all sensory experience and memory is this level Steiner calls pictorial. Not necessarily painted pictures, but feeling-pictures, gestalts of experience.

Practicing with the Pen

So let’s play with this. First do Peace, or Rest, or Blue-Red, or a melody—whatever practice you choose. Breathe with it until you establish some balance.

Then take your pen out so it’s easy to see. I’m to ask you to shift your gaze to the pen and try to just look at it in an open way and then see if you can somehow bring that inside, and then we’ll dialog about that.

Dialogue: Questions and Answers

Q: It’s like water… waves… going out, then they came back. I started entering the idea. A wave went out, another came back, but the first wave was continuing.

A: Repetition of that eventually builds a rhythm you can surf on. At first you’re sending things out, then waiting. After a while you realize: I was in-breathing. That’s what generally happens: pushing, then when it gets subtle, you feel the mingling of spaces. If you can sustain that, without dropping into, “Oh, that’s relaxing,” then you’re really helping with stress. Just staying in that, without tension.

Q: I used the word Peace. I said it about ten times, and I couldn’t decide if I should out-breathe with the word or in-breathe. But I felt like I expanded physically outward after I said it.

A: Yes. The physical thing is important. Very often when you do this you’re releiving your nervous system of a burden that’s been there a while. Suddenly it’s like: “Oh yeah, remember when you put that down there? You’re going to deal with this now.”

So it comes up as an itch, a twitch, a pain, stiffness. If you continue, it may get worse at first.

Massage therapists know this: they come up into a stiff area and lift off, slowly. You can do the same with your attention. Find a tense spot, let the impulse of Peace go through it, lift it off, send it out.

You’re saying to your body: I’m home now, I’ll take care of this.

Your body says: Yeah, but I’ve been holding this a long time, I’m afraid if I let go your head might snap, so I’m holding on.

There’s the dialogue. In a gentle way you say: Thank you. Peace. And you stay with that area until you feel the sigh, the okay, I’ll trust you.

That’s porosity. Opaque places in your body become porous again.

In martial arts, in Tai Chi, they call it tui shou—push hands. You’re feeling energies, pushing, receiving, listening. Eventually the stuck place says: Okay, I trust you. I’ll join the body again.

That expansion of trust expands consciousness. Movements of the day become perceptible as patterns. You reclaim parts of the life body that had been squeezed by constant pressure from the astral body.

Steiner says: the astral body, pressing too long, weakens the etheric body, so it penetrates into the physical. That’s pain.

This exercise says to the life body: Expand here. I’m home. The astral content won’t hurt you while I’m watching.

And then consciousness expands. If the phone rings at that moment, you feel your sheaths go boink-boink-boink-boink-crash. That’s a symptom you were in your life body.

Actors know this. Shoulders, glutes—places we store things. So we are puffing the ether body out, making it porous again, like the Pillsbury doughboy.

Q: I was looking at a carpenter’s pencil. What I noticed were all the experiences of what happens in the day with the pencil. So I didn’t see the pencil, I saw everything I do with it.

A: That’s around it, yes. Were you able to get an image of it?

Q: Not an image, just the day’s experiences.

A: So after that, if I asked you to describe the pencil, could you?

Q: Yes, because I know what it is.

A: Right. But what you’re describing are associations around it. There’s a field of associations around every object. In the center of that field is the image itself. Associations radiate out. You can loop back through them to the thing itself. So those pictures that come up are around that area where your attention is, and in that is a seed of this that you would use now to describe it. If you follow those associations back, and say: What’s really behind this pictorially, or however you were doing it, go back, they all go back to the same thing. And that thing, eventually you want to just to the thing and not the associations. Does that make sense to you?

Q (another): My experience was what it could do for me. How many poems I could get out of it.

A: That’s association too. The struggle is to hold on to the actual sensory experience without associating. Buddha taught a method called looping: when your thought morphs into association, trace it back to the starting object. That strengthens representation.

Q: What qualities should we hold when focusing?

A: Just say: pencil. Just the facts, ma’am. Rudolf Steiner called it cultivating boredom. That’s why we choose something boring. So what comes up isn’t “cool pencil thoughts” but our attention, working to recreate the image.

Q: When I looked at the pen, I pictured it, but soon lost interest. Then I saw the ground. My interest was in the shifting back and forth.

A: That’s valid. The image itself breathes—salt to sulfur, sulfur to salt. It’s not a pathology when the image dissolves. Unless living itself is a pathology. What matters is to witness the breathing consciously. That’s mercury.

Q: I had two insights. One was a clear visual recreation. The other was a fuzzy warm space where the pen “wasn’t.”

A: That may be you seeing not just the object but also the processing center in your brain—the calcarine cortex, or the limbic reticular system. Sometimes the practice shows you where you’re seeing.

Q: Where does balance come in?

A: Balance comes in through rhythm. Salt: the object. Sulfur: the inner image dissolving. Salt: the object again. It’s breathing. Old schools demanded rigid one-pointedness. But the modern task is fluidity, to form an organ of fluidity. That is mercury.

Q: So you want it to fluctuate?

A: Yes. This is subtle. Stress at another level is always: Who’s in control? If I’m in control of my car and someone makes me lose control, I’m unhappy.

So rhythm replaces power. That’s the new mystery teaching. Rhythm replaces power. The heart is the organ of mercury, the heart is the specialist in rhythm. When the heart can see, I don’t need control to be at peace.

Q: My interest came not in the pen or the ground, but in their breathing together.

A: Yes. That’s mercury. Interest is the vehicle between the two.

Q: What would make the pen more interesting?

A: Interest doesn’t come to us—it comes from us. We can ask: what’s its biography? How was it made? That’s the Gospel of John: “Everything that was made was made.” To perceive that everything has a becoming. That’s respect.

So: homework. Form the image of the pen. Hold it. Then ask: What did this look like just before it became this? What’s its biography?

Q: When I looked at the pencil, I didn’t really see the pencil itself. What I noticed were all the things I do with it—the experiences of the day, the tasks it helps me with. I wasn’t holding an image of the pencil like a picture, but rather all these associations: writing, marking, making things. It felt like I was in the middle of all those activities rather than looking at the thing itself. And I wonder, is that still the image? Or is that something else?

A: That’s a really important observation, because what you’re describing are the associations around the pencil. Every object has a field of associations—memories, habits, uses, feelings—that surround it. Those associations are real, but they’re not quite the image itself.

The work here is to notice that when you try to hold an image inwardly, it often dissolves into those associations. You start with the pencil, and suddenly you’re thinking about your poetry, or your bank account, or your grocery list. That’s the morphing process. Buddha actually gave a name to the practice of working with this: looping. He told his disciples, “If you find your thoughts running off into associations, trace them back through the sequence of steps until you return to the thing you started with.” So if your pencil thought morphs into poetry, and poetry morphs into money worries, and money morphs into color patches or moods, you put up a little flag and say, Whoa, I’m out here somewhere, and loop back toward the pencil.

This is very effective, because the inner image—the representation, in the physiology of perception—is always in danger of dissolving into associations. By looping back, again and again, you slowly bring the associations closer in, until they no longer sweep you away.

Now, here’s the subtle part: the image itself is going to breathe. Outward to salt—the pencil, as it is. Inward to sulfur—the inner representation that wants to dissolve. That breathing is not a pathology; it’s the normal life of an image. What we’re learning to do is to witness that breathing consciously, to ride with it instead of getting lost in it.

And that’s why we choose something boring like a pencil. Steiner called this “cultivating boredom.” The pencil itself isn’t fascinating. It’s just salt, just there. That way, what comes alive is not “cool pencil thoughts,” but the activity of our attention as we try to re-present the pencil inwardly. That designated attention, sustained rhythmically, is what builds capacity.

If you can learn to hold even that boring object with interest, to trace back through associations, to witness the rhythm of salt and sulfur, then you start to discover a field-seeing. Not a photographic picture, but a felt image—an “as if” experience—that carries the presence of the thing itself. That is what we’re after.

So there’s the object itself, and then there’s the inner representation. What happens is that some details stand out more than others. Those are seeds of further interest.

When we look with the heart, we ask: What was this like before it became what it is now? That opens biography. And when we get a feeling of evidence for that sequence, that’s Steiner’s “percept meets concept.”

In that is freedom, respect, love, energy, wisdom, mercury. Because we’ve found the link between ourselves and the thing. Everything has a biography. When we’re interested in their becomings, the whole creation begins to speak.

The Seed of Practice

So the blood and the nerve, sympathy and antipathy, salt and sulfur is really about rhythm. Mercury. The question is always how to find balance in the middle of life’s pushes and pulls.

Stress is not the enemy. Stress is the world knocking on the door, asking us to grow. If sympathy and antipathy are in balance, stress lifts us. If they’re not, it breaks us down. The task is to cultivate a practice so that when the knock comes, we have a rhythm to meet it with.

That practice doesn’t have to be complicated. It can be as simple as saying “Peace” and noticing what happens in the silence after. It can be holding the image of a pen and watching how it breathes in and out, salt and sulfur, dissolving and reappearing. The point is not the pen, not the word. The point is to cultivate attention to begin building a little reservoir of rhythmic forces you can draw on when life gets rough.

In time, this becomes capacity. Instead of stuffing things into the bag of resentment or reaching for the .38 under the seat, you have something to draw on. You can say, Peace. Rest. I’m here. I can meet this. That’s rhythm replacing power. That’s the heart learning to see.

So the promise I made at the beginning, that you might leave with some seeds for managing stress or even pain, this is it. A seed of practice you can take into your own life and grow into a rhythm that sustains you.

And that’s really the alchemy of it. Sulfur and salt, balanced in the rhythm of mercury. Blood and nerve learning to speak to one another. That’s the work.

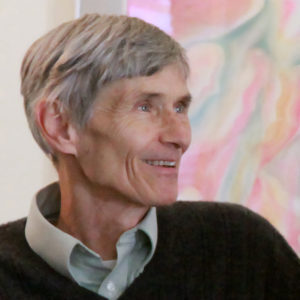

Dennis Klocek

Dennis Klocek, MFA, is co-founder of the Coros Institute, an internationally renowned lecturer, and teacher. He is the author of nine books, including the newly released Colors of the Soul; Esoteric Physiology and also Sacred Agriculture: The Alchemy of Biodynamics. He regularly shares his alchemical, spiritual, and scientific insights at soilsoulandspirit.com.

3 Comments

Leave a Comment

Similar Writings

Memory, Fantasy and Imagination

Human neurological patterns represent a cascading hierarchy of organ responses to sensory stimuli that come from the environment. Sensory inputs through the sense organs impact the nervous system directly. The direct nerve pulses then cause secretions of hormones into the blood as secondary responses to light, sound, smell and movement. In the brain the pituitary…

I absolutely loved this in so many ways. It related to a deep part of myself. Thank you

How beautiful! And I feel this is also doable, after so many failed attempts at meditation. Your work on so many topics-issues, and the supportive presence of your son—a blessing indeed.

So grateful for your generous and timely sharing,

Joellen Koerner

thank you for all this work. Im relieved to finally understand the meaning of sympathy and antipathy and the sulfur and salt sensation. Finally it’s all together living in my thinking.